FRANCE

In the period 2019-2050 the share of 65+ people in the French population is expected to grow from 20% to 26.6% (compared to an increase from 20% to 28.5% in the EU-28), with most of the growth happening before 2030. At the same time the share of 85+people will expand by more than a factor 2 from 3.2% to 6.5% (EU-28: 2.7%-6.1%).

Over the same period, the old-age dependency ratio measured as the percentage of 65+ compared to the population of 15-64-year olds will rise from 31.6% (EU-28: 30.5%) to 47.6% (EU-28: 55.3%).

Life expectancy for men and women at age 65 is projected to rise from 19.6/23.6 years (EU-28: 18.1/21.4) in 2017 to 23/26.6 years (EU-27: 22.4/25.6) in 2060.

Under an assumption of no policy change the Ageing Report scenario suggests that public expenditure as share of GDP would rise from 1.7% to 2.6% (EU-27: 1.6%-3.1%) by 2070. The impact of a progressive shift from the informal to the formal sector of care in France would entail an estimated increase by 76% in the share of GDP devoted to public expenditure on long-term care (128% on average for the EU27).

The French public provision of long-term care (LTC) to the dependent elderly and the disabled relies on a two-pronged system. On the one hand, the health insurance scheme covers the cost of health care provided in an institutional setting to the dependent elderly or disabled patients. It also finances LTC units in hospitals, as well as nursing care provided at home and these costs are paid for directly by the health insurance scheme, i.e. patients do not need to advance the money themselves.

On the other hand, two schemes, essentially financed by the state and by local authorities, provide social benefits to the dependent elderly and to the disabled to help them meet some of the costs of care that are not covered by the health insurance, whether that care is provided in institutions or in a domiciliary setting.

For the disabled, a new benefit came into force in January 2006, called the Prestation de Compensation du Handicap – PCH − (Disability compensation benefit) which aims to better cover the needs of the disabled irrespective of the disability, age or lifestyle of the person. This benefit is intended to help cover the needs of the person regardless of whether those needs have to do with professional insertion, home adaptation, human and technical aids, etc.

The dependent elderly is also entitled to receive the Allocation Personnalisée d’Autonomie – APA (Personalised Autonomy Benefit), which is a universal benefit for people over 60 that came into force in 2002. This benefit is calculated based on a “help plan” designed for each individual, on the basis of the assessment of the person’s needs. The APA benefit is intended to cover part of the cost of the “help plan”, the rest (about one quarter of the total amount on average) is paid by the beneficiary through user fees which increase proportionally to the elderly’s income. Elderly people with an income below EUR 689.50 per month do not pay user fees. The amount of the benefit thus varies both according to the person’s level of dependency (established by a socio-medical team) and according to the elderly’s financial resources.

On December 31st 2011, there were 1,200,254 people above the age of 60 who received the APA dependency benefit. 60% of APA beneficiaries lived at home, and 40% in special accommodation for the elderly. The average amount of the help plan granted to people receiving domiciliary care was EUR 487 per month (of which around 20% are covered through user-fees), and 517 euros for institutional care (of which around 33% are covered through user-fees).

The fast (and partly unforeseen) increase in the number of APA recipients since its introduction in 2002 has put a strain on public finances, especially for local authorities (départements) who finance over two thirds (72%) of the cost of the APA, the rest being covered by the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy – CNSA.

Between 2007 and 2011, the institutional capacity for LTC increased by 5,3% and the institutional care capacity (number of beds) for inhabitants aged 75+ amounts to 101 per 1000, but strong geographical disparities exist across the country.

The 2015 Act on adapting society to an ageing population marks a turning point in the design of policy in the LTC sector. The aim is indeed to move away from a health and social approach to old age focused on the concepts of dependency, which dates back to the 1990s. The approach behind this law was to tackle the issue of ageing in a comprehensive manner, integrating the notions of healthy ageing and prevention (Delaunay, 2017).

The APA is based on three pillars:

- Anticipate the loss of autonomy, which comprises financing action on preventing and combating isolation among old people (EUR 185 million in 2017);

- Adapt society to ageing, which includes the launch of a plan to adapt 80,000 private housing units by 2017, refurbish residential homes (foyers logements) now renamed ‘homes for independence’ (EUR 84 million in 2017);

- Support older people who are facing a loss of autonomy, with a priority given to home-based care (EUR 460 million in 2017).

Number of carers

As is the case in many European countries, the available data regarding the prevalence of informal care in France builds on various – and sometimes conflicting – sources. The only official figure emanates from the Directory for research, studies, evaluation and statistics (Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques / DREES) and dates back from 2008. According to this study, there would be 8,3 million informal carers in France (12.9% of the population), among whom 4,3 million provided regular care at home to a person over 60 years old[1]. The same study anticipates that, in 2030, 25% of people in employment will also assume caregiving responsibilities.

A more recent study by Fondation April et BVA (2017) assesses the number of carers in France at 11 million, i.e. 1 person out of 6 providing daily assistance to a dependent person, as a result of old age, illness or disability[2].

The value of informal care in France, as regard the savings realised thanks to the contribution of carers to society, is estimated at 11 billion euros per year[3].

Recognition and definition of carers

While the family is the main provider of care for the elderly, there was – until very recently – no real ‘care for the carer’ policy in France. But this does not mean there is no attempt to contribute some support to informal carers.

In 2015, the Act on Adapting society to an Ageing Population extended the definition of the term ‘carer’ to people outside the family. It recognized the French term ‘proche aidant’ (which has no real equivalent in English and could be translated as ‘close carer’) as follows: “The Proches Aidants (carers) of an elder person are: their spouse, the partner with whom they have concluded a civil solidarity pact, a cohabitant, a parent, or ‘ally’ defined as family carers, or a person living with them and with whom they maintain a close and stable relationship, who provides them with regular and frequent care, in a non-professional capacity, to carry out all or part of the activities of daily living.” (article 51).

The Act on Adapting Society to an Ageing Population also confirmed and extended the role of the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy (CNSA) as the national agency in charge of the management and follow up of the elderly care policy. When it comes to informal carers, the agency suggests to fund the training of carers, a support mission for the creation of the “Funders’ Conference for the Prevention of elderly people’s loss of autonomy” (see below), as well as the development of a frame of reference to define the needs of carers providing support to older dependent people or to any other person in loss of autonomy.

In October 2019, the French government launched a comprehensive national Strategy to support informal carers. The Strategy is supported by a 3-year budget of €400 million (including €105 million for respite care). A committee piloted by Ms. Agnès Buzyn, Minister of Solidarity and Health and Ms. Sophie Cluzel, Secretary of State in charge of People with Disabilities will meet on a bi-annual basis to monitor the implementation of the Strategy.

The strategy builds on 6 priorities in favour of carers:

Priority 1 – Break carers’ isolation and provide them with daily assistance

Priority 2 – Create new social rights for carers and alleviate their administrative burden

Priority 3 – Allow them to reconcile their professional and personal responsibilities

Priority 4 – Further develop and diversify options for respite care

Priority 5 – Focus on carers’ health needs

Priority 6 – Support young carers

These 6 priorities are spelled out through a list of 17 measures which are described in the following sections of this document.

Identification of carers and assessment of their needs

A recent survey carried out by Fondation April (2019)[4] allows to delineate the profile of a typical informal carer in France.

- On average, respondent carers are located 226 kms (140,43 miles) away from the care recipient,

- 62% of them are in employment,

- 56% are women,

- 64% report sleeping disorders,

- 74% state that they suffer from stress, feel guilty, and exhausted,

- 90% provide care to a family member,

- 20% report a very heavy workload,

- 31% declare that they tend to delay or even give up their own care,

The lack of information and heavy administrative burden, the need for respite and the need for support to prevent exhaustion were some of the key learnings of the survey.

Multisectoral care partnerships

French support services are currently structured through various departments. The primary source of referrals is the Town Hall which deals with requests via different services:

Besides the provision of information and counselling

- CLICs (Local Information and Coordination Centres / Centres Locaux d’Information et de Coordination), providing information to people aged 60 years old and over and their carers

- CCAS (Centre Communal d’Action Sociale / Community Centre for Social Action), which is usually presided by the mayor and is in charge of promoting social inclusion and coordinating social policy in the city;

- MAÏAs (Méthode d’action pour l’intégration des services d’aide et de soin dans le champ de l’autonomie / Method for the integration of support services in the area of autonomy), which is a new approach seeking to develop one stop shops for the provision of integrated support and care to people aged over 60 years old and at risk of a loss of autonomy. This new approach will be set up and implemented as of 2022, following the measures announced by the French Government in October 2019.

Access to information and advice

Since 2013, (potential) carers and people in need of care can access information about their rights and the services available to them though a network of 600 CLICs (Local Information and Coordination Centres / Centres Locaux d’Information et de Coordination) disseminated throughout the country.

Besides the provision of information and counselling, CLICs can also offer additional support services, such as:

- Assessing the needs of the care recipient,

- Developing a support plan, in collaboration with the care recipient and the informal care,

- Monitoring the implementation of the support plan, in coordination with involved professionals,

- CLICs increasingly expand the scope of skills and expertise made available to their ‘clients’, including through the inclusion of social workers, physiotherapists, nurses, doctors, etc.

CLICs also organise conferences and workshops on prevention of dependency (e.g. Alzheimer’s), domiciliary services, home adaptations for seniors, carers’ support, nutrition, memory loss, fall prevention, mutual carers’ support groups, carers’ training, individual counselling meetings with professionals (social workers, psychologists).

On online information platform is also available (www.lesitedesaidants.fr), which provides carers with advice on existing rights and services as well as on the prevention of all negative impact of informal care on carers themselves. The platform was set up by Malakoff Médéric Humanis, a non-profit health insurance provider.

Under priority 1 of its national Strategy, the French governments announced the creation of a national helpline to support carers (as of 2020) as well as the development of a network of information hubs targeted at carers. This will be complemented by the launch of an online information platform in 2022. Finally, measures will be developed to foster the provision of support by care professionals and fellow carers – these nevertheless are yet to be clarified.

Carers’ mental and physical health

A dedicated Public Health survey will be launched in 2020 to collect information about the health risks and challenges faced by informal carers. In addition, care professionals will be invited to pay more attention to informal carers in their interactions with care recipients and to identify carers in the shared medical file (dossier médical partagé DMP).

Access to respite care

Respite care has been improved with the development of day care centres, and a ‘right to respite’ was introduced in the 2015 Act on adapting society to an ageing population. This right to respite care can be activated once the threshold of the care recipient’s assistance scheme, as described in the APA, is reached.

The right to respite can then be supported through a financial help of up to EUR 500 per year, which can be used to pay for:

- A day or night care centre,

- Temporary accommodation in an institution or in a foster care setting, or

- Home care services.

The national Strategy to support informal carers includes an action plan to reinforce and diversify the offer of respite care services, which is accompanied by an additional budget of €100 million for the period 2020-2022.

Social inclusion of carers, access to education and employment

In France, public interventions targeted at informal carers primarily aim to support carers in their activities rather than providing them with financial compensation. Besides, while the APA can be used by beneficiaries to pay a relative (except for spouses), this remains a marginal option (8% of beneficiaries, Court of Auditors 2016).

Work-life balance for carers is therefore at the core of preoccupations. The DREES survey carried out in 2008 estimated that 4.3 million carers provide regular help to one or more relative over 60 (Soullier, 2011). A typical carer in this group is a woman of 58 years of age and women represent 57% of carers of older people in the country. The proportion of female carers even increases to 74%, along with the level of dependency of the cared-for person (Dubois, 2011). The survey also shows that 46% of carers are retired, 39% have a job, and 15% are out of work. 11% of carers have reorganised their professional lives by reducing their working hours, resorting to sick leave or changing jobs. Considering the difficulty for carers to combine work and care and the growing participation rate of women between 50 and 64 in the labour market (up to 61.1% in 2015, see INSEE, 2017), work-life balance is of particular importance for women and gender equality.

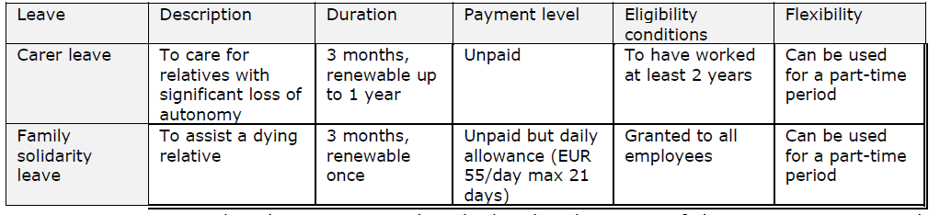

Many of the forms of leave that have been created to support the working carers of disabled and older people do not discern between both populations and do not take into account the age of the care recipients. A distinction must nevertheless be made between:

- a specific leave scheme for parents of disabled children, i.e. the Parental Presence Leave; and

- less generous forms of leave created more recently for dependent adult relatives, i.e. the Family Solidarity Leave (congé de solidarité familiale) and Family Support Leave (renamed Carer’s Leave in the law on adapting society to an ageing population of December 2015).

The Family Solidarity Leave is open to “every employee whose parents, siblings, descendants or cohabitant suffers from a life-threatening pathology or is at an advanced or terminal stage of a serious and incurable ailment”. The leave allows an employee to suspend their professional activity to care for someone in loss of autonomy, for a period of up to three months (renewable). It cannot be deferred or denied by the employer. During this time, the carer can benefit from the daily home support allowance (allocation journalière d’accompagnement à domicile, AJAP), payable by the social security.

The Carer’s leave (congé de proche aidant) is designed for the care of an infirm relative or a relative coping with a loss of autonomy. Carers can ask their employer to temporarily interrupt their professional activity, while keeping their position and rights in the company. This leave can last up to three months (except if a collective agreement exists) and can be renewed. It is however not compensated by the employer.

Carer leave: concerns both elderly and disabled people.

A new piece of legislation was adopted in May 2019 to promote the recognition of caregiving and promote the use of the Carer’s leave through compensation and more business negotiations. It also seeks to secure the social rights of the carer by standardizing the situations across different social security schemes, by putting in place a system involving health and social services, by issuing a card to identify carers (especially with health professionals), and by developing a carer’s guide and web-based information and guidance[5]. This forms part of the national Strategy to support carers.

As of November 2019, the periods of Carer’s leave (congé de proche aidant) will not negatively impact the calculation of unemployment benefits anymore. As of January 2020, the length of service will be removed from the list of eligibility criteria to access a Carer’s leave. The compensated Carer’s leave will be introduced for employees, freelance workers, civil servants and the unemployed as of October 2020. In addition, the leave will be automatically taken into account in the calculation of pension rights without any additional administrative requirements.

The Parental Presence Leave (Congé de présence parentale) and the accompanying daily allowance will be accessible per half day as of January 2020. Return to employment for long-term carers will also be facilitated and support to carers will be added to the list of compulsory topics for collective bargaining and of corporate social responsibility.

Although there are no specific data on how many working carers take advantage of carer leave to achieve a satisfactory work-life balance, a recent survey (Sirven et al., 2015) suggested a very low-take up of this type of leave, at only 7% of interviewees. Most carers (between 50% and 80%) were unfamiliar with the leave provisions. In fact, carers tend to use standard leave (sick leave) or even annual leave, rather than specific carer leave, which is either unpaid or with a low allowance.

Flexible working conditions for working carers also form part of the options for better work-life balance (Knijn, Da Roit, 2013). In France, there is no legal obligation for employers to provide flexible working time to informal carers, but a law introduced in 2005 includes positive action in favour of personalised working time. This arrangement should allow working carers to organise their arrival and departure from work within time slots agreed by the employer, provided that a certain number of working hours are fulfilled. The availability of this provision nevertheless differs depending on whether the carer is an employee, civil servant or works in the private sector. Generally, the measure seems more frequently available in the public sector. A shift towards part-time work (50%, 60%, 70% or 80% of full time) can also be requested for periods of between six months and a year, renewable, and limited to three years.

Lastly, it is worth noting that the national Strategy to support informal carers announced by the French governments in October 2019, also includes plans to raise awareness about the existence and situation of young carers among education professionals. Furthermore, measures for flexible pace of studies will be introduced as of the end of 2019to accommodate the needs of students with caregiving responsibilities.

[1] Enquête Handicap-Santé 2008, DREES

[2] Baromètre 2017, Fondation April et BVA

[3] Université Paris-Dauphine and Share data

[4] Cinquième Baromètre des aidants, Fondation April, 2019

[5] UNECE Policy Brief on Ageing No. 22, September 2019

- Aidants: une nouvelle stratégie de soutien, French government’s website, 2019

- The 2018 Ageing Report, Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2016-2070), EC, 2018

- ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care, France, EC, 2018

- European Network on Quality and Cost-Effectiveness in LTC and Dependency Prevention, Country Report France, B. Le Bihan et A. Sopadzhiyan, 2017

- ESPN Thematic Report on work–life balance measures for persons of working age with dependent relatives, France, 2016

- Joint Report on Health Care and Long-Term Care Systems and Fiscal Sustainability, EC, 2016

- Adequate social protection for long-term care needs in an ageing society, European Commission, 2014

Last Updated on June 28, 2023