Why carers count?

Europe’s overall increase in life expectancy and ageing demographic is generating a growing incidence of age-related conditions, a growing demand for care in all age groups and a serious sustainability challenge for care systems. This is exacerbated by an ageing EU health and social care workforce, problems with staff retention due to demanding working conditions and relatively low pay in some occupations, as well as the need for new skills and competences as a result of new care patterns and the rise in new technologies. These challenges are consistent across EU member states.

Against this backdrop, community care has become a prominent EU priority in the last few years and the shift towards home-based care is seen as a practical measure to contain the costs of services while also supporting widespread preferences among (older) people1. All of this puts more and more pressure on informal carers who – in most European countries – already provide a large part of Long-Term Care for dependent people.

In Europe, 80% of Long-Term Care (LTC) is provided by informal carers. In 2019, public expenditure on long-term care amounted to 1.7°% of the Union’s GDP. This is less than the estimated value of hours of long-term care provided by informal carers, estimated to be around 2.5°% of the GDP of the Union (1).

The value of informal care in Europe is not only a matter of finances. Informal care and solidarity also have an intrinsic value from a moral standpoint, i.e. standing and caring for vulnerable groups (e.g. people who are chronically ill, persons with disabilities and frail older people) not because of any personal interest, but because they need this support. Caring, and its impact on both those who carry out the role and those who receive care, engages civil, political as well as socio-economic rights. The provision of the latter in particular, requires positive actions by the State and investment of public resources.

From the above, it is clear that carers are an inherent as well as an indispensable part of the provision, organisation and sustainability of health and social care systems. They will become even more important in view of the changing health and care needs, due to demographic ageing and the increasing prevalence of frailty and chronic conditions.

(1) Van der Ende, M. et al., 2021, Study on exploring the incidence and costs of informal long-term care in the EU.

What are the issues at stake?

Europe’s overall increase in life expectancy and ageing demographic generate a growing incidence of age-related diseases and demand for care. In Europe, 80% of all care is provided by informal carers – i.e. people who provide unpaid care to someone with a chronic illness, disability or other long-lasting health or care need, outside of a professional or formal framework. The contribution of these carers constitutes a great resource for our society but their role is not always recognised. Delivering a wide range of support services such as personal care, housekeeping, transportation, care and financial management as well as emotional support, carers often offer the most comprehensive and desirable option for people in need of care.

Caring for a loved one can be a source of great personal satisfaction but it does create its own set of challenges. These can include physical and mental health problems, a feeling of isolation, difficulty in balancing paid work with care responsibilities, perhaps even financial worries as social provisions are cut back. Advances in medicine also mean that carers find themselves having to deliver more and more sophisticated levels of care, with very little training and minimal support.

In Europe, 80% of all care is provided by informal carers

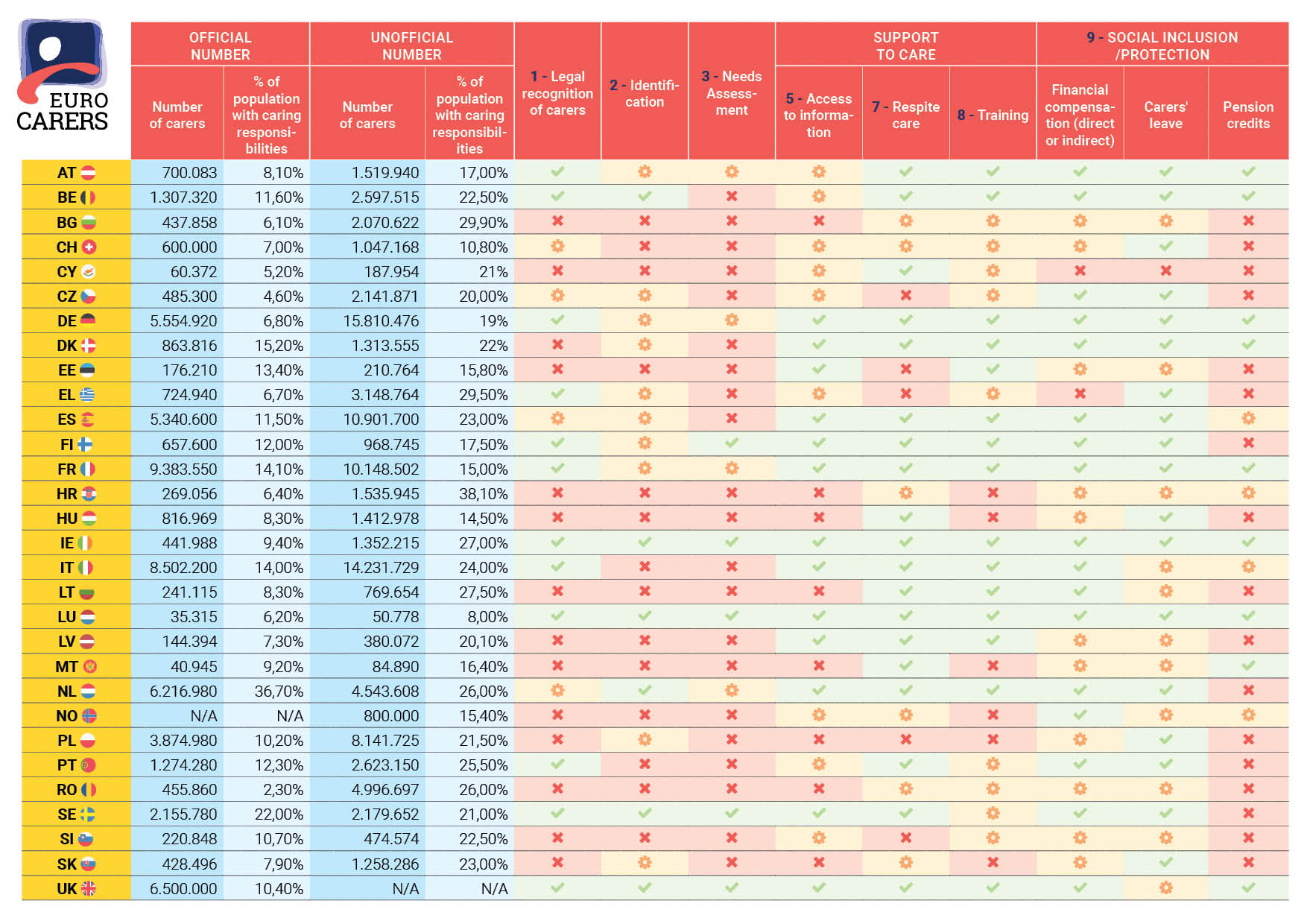

Number of carers and existing support measures across the EU

The unofficial data concerning the proportion of the population with informal caring responsibilities emanates from the 2022 EIGE survey of Gender Gaps in Unpaid Care, Individual and Social Activities

Last Updated on October 18, 2024